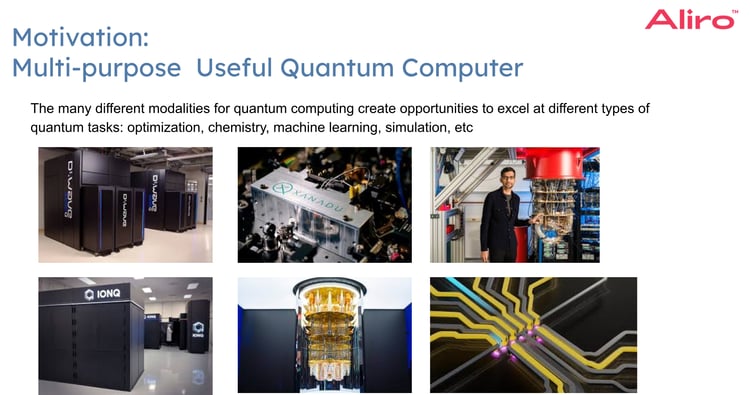

Today’s quantum computing ecosystem is very diverse. And it’s likely to stay that way! There are many different approaches to building a quantum computer, and each approach has its strengths and challenges:

Quantum annealers (example: D-Wave)

D-Wave’s systems use superconducting qubits, but in an annealing architecture that is used for large-scale optimization problems. These types of machines excel at setting an initial state and slowly cooling the system to find a global minimum of a cost function, rather than performing gate-based algorithms.

Photonic quantum computers (example: Xanadu, PsiQuantum)

Xanadu is a boson sampling machine, and is progressing toward full gate-based systems. PsiQuantum is targeting a large-scale quantum computer using photons. Using photonic qubits is advantageous; they’re more easily scalable through networking because they're already integrated with optics and lasers and detectors.

Superconducting gate-based systems (example: Google, IBM, Rigetti)

These are the types of quantum computers that look like intricate chandeliers, and they’ve been the leading approach for many years. Superconducting gate-based systems use tiny aluminum circuits patterned on a chip. These circuits act like inductors and capacitors, and the qubit’s state is stored in the electrical current flowing through them. Because these devices only work at extremely low temperatures, they’re operated inside large dilution refrigerators. It’s difficult to build chips with many more than 100 to 200 qubits due to fabrication limits and wiring complexity. Scaling beyond that requires new approaches, including networking multiple smaller quantum processors together.

Trapped ions and neutral atoms (example: IonQ, Quantinuum, Atom-based platforms)

Atoms and ions are arguably the most “natural” qubits: quantum mechanics was literally discovered by studying atomic spectra. These types of quantum computers exhibit longer coherence times (seconds instead of microseconds), high-fidelity gates, and often all-to-all connectivity within a register. Compared to superconducting gate-based systems, these trapped ion / neutral atom systems are slower in operation.

Spin qubits (semiconductor platforms)

Spin qubits are promising for scalability and potential closer integration with existing semiconductor processes. Their performance is earlier-stage compared to superconducting or ions, but their scaling path and optical interconnect potential are compelling.

Along with their particular strengths and weaknesses, each of these modalities has its own “sweet spot” of computation. For example:

- High-speed, measurement-heavy algorithms (like some variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) workflows) may favor superconducting qubits.

- High-precision quantum chemistry or error-corrected logical qubits are seeing strong results on ions and atoms.

- Large optimization problems map naturally to annealers.

This variety in quantum computing isn’t going away. It’s more likely that multiple modalities will be successful in the long-term for different classes of problems, and that these modalities will be co-located in future quantum data centers. You might be wondering, if quantum networks will eventually span cities, countries, and continents, why worry about co-locating QPUs in the same building or campus?

The answer is physics and performance! Long-distance quantum networking (hundreds or thousands of kilometers) is essential for the future quantum internet and for applications like Quantum Secure Communication. However, for distributed quantum computing, where you want multiple QPUs to act effectively as a single logical machine, some factors are really magnified by distance:

- Loss in optical fibers.

- Gate speeds and timing.

- Entanglement generation rates and fidelities.

- Tight, fast classical feedforward between measurements and operations.

All of these are easier when QPUs are co-located in a quantum data center with well-engineered optical paths, shared infrastructure, and carefully controlled environments. Co-location also offers practical advantages. The ability to share resources like cryogenics / cooling, power, physical security, optical switches, transducers, and Bell-state measurement devices is both convenient for maintenance and cost effective. There’s a lower cost per qubit and per experiment as quantum computers scale when resources can be shared.

Quantum Networks bring everything together

Quantum networks bring all of these pieces of scaling quantum computation together. To make heterogeneous quantum data centers work, a quantum networking layer capable of moving quantum states between different processors, supporting multiple qubit encodings (photonic, atomic, superconducting, spin), and maintaining entanglement and fidelity as states are converted and routed. This requires a coordinated set of components, including quantum photonic switches that serve as the central interconnect fabric, transducers that translate quantum states between domains, frequency converters that align wavelengths across devices, quantum memories that buffer states for repeater-style architectures, and precision timing, interferometry, and polarization control to keep everything stable and synchronized. Managing this hybrid classical–quantum system, full of components with distinct physical requirements, is where simulation and orchestration become essential.

At Aliro, one lesson we’ve learned the hard way is that hardware is not the first bottleneck. Getting hardware is straightforward compared to choosing the right architecture and components, aligning timing across devices and nodes, and designing protocols and control logic that behave well under real-world noise and loss scenarios.

We recommend that organizations start with quantum network simulation before committing to hardware, and have many resources to help organizations on their path to QPU networking.

For more on getting started with quantum networking to enable quantum-powered data centers, check out our report Aliro Simulator for Quantum-secure Data Centers, HQs, and Clouds